Two Great Transformations

Part I: A review of Branko Milanovic

Over the winter I read two books that deal with sweeping changes in the last half century: Branko Milanovic’s The Great Global Transformation: National Market Liberalism in a Multipolar World (Allen Lane, 2025) and Odd Arne Westad and Chen Jian’s The Great Transformation: China’s Road from Revolution to Reform (Yale UP, 2024). I initially intended to write only about Milanovic’s book. Yet after picking up Westad and Chen in a bookstore, I realized that both books share a concern with how China’s rise fits into global economic history and the international order in the late twentieth century. Hence my decision to consider them together. As the review began to run rather long, I split it into two halves: Part II will follow next week.

Sometimes reaching back to old classics helps to understand the present. Karl Polanyi’s 1944 The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Times analyzed how the 19th-century world order was undone during the interwar years of the Depression by a backlash against unfettered laissez-faire policies, which Polanyi characterized as the “disembedding” of the market. In the early 2010s I wrote my Cambridge MPhil dissertation on Polanyi’s economic journalism during the Great Depression and how this writing informed what would eventually become The Great Transformation. So the similarity in the two book titles immediately intrigued me.

Both Milanovic and Westad and Chen acknowledge their debt to Polanyi. They follow the Hungarian thinker in portraying crises as occasions for shifts in political and economic norms. The nature of the crises on which they focus is different. Milanovic’s book is a worldwide study of how neoliberal globalization in the 1980s-2000s was undone by nationalist political insurgents in the 2010s and 2020s. Westad and Chen are concerned with China’s path from Maoist socialism in the 1960s to the Reform and Opening Up era that started in the 1980s. But the underlying structural dynamics are similar: a set of pressures and stresses in a developing system explode into the open, forcing a shift in the dominant political-economic order.

Global convergence and national divergence

Milanovic’s book follows his previous books Global Inequality (2016) and Capitalism, Alone (2019), but it is more narrative in style than the former and more interested in politics and ideology than the latter. Milanovic takes as his point of departure a finding he has already examined in his previous studies: the economic convergence of Asian economies with the rich Global North. This process, he argues, is easily the most significant thing to have happened in economic history and in the global distribution of wealth and income during the past fifty years.

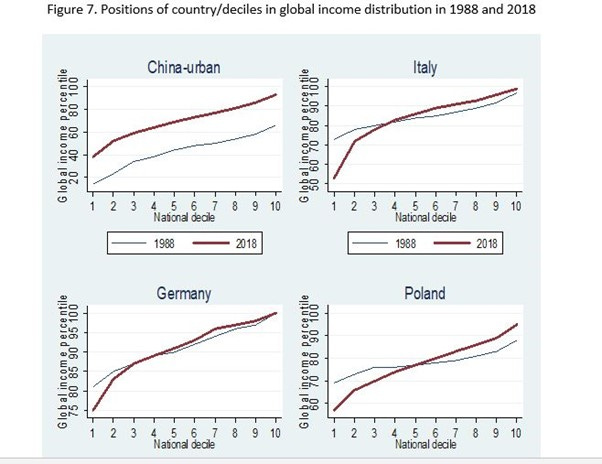

Driven above all by the rise of China and India, Asia’s convergence has now resulted in a situation in which the upper tiers of the Asian bourgeoisie are richer than the poorest citizens of the West. The upper decile of urban Chinese income earners, for example, is now ahead of the European lower class, equal in income with the U.S. working class, and fast catching up with the U.S. middle class.

From the point of view of global equity and justice, the rise of Asia is laudable and welcome. Globalization has produced real winners among non-elites around the world. But this shift, Milanovic suggests, has had destabilizing effects on Western democracies, whose poorest inhabitants have found themselves sliding down the global income distribution at a precipitous pace.

Italy is a good example. In 1988 the country’s entire population inhabited a section of the global income distribution between the 73rd and 97th percentile of the world. Rich Italians were among the best-off anywhere in the world. But even the poorest Italians were in the late 1980s, when the country’s economy was still recording high growth rates, still richer than nearly three quarters of the world’s population.

By 2018, this situation had worsened dramatically. Milanovic shows that the Italian lower and upper income bounds are now at 53 and 99 percentiles of the global income distribution. The conclusion is that Italy is now a nation so unequal that it occupies nearly half of all the wealth outcomes it is possible to find in the entire world.

A similar process (Milanovic calls it the “positional decline of the Western middle class”) has taken place in the entire West. It is not so much the rich who have improved their position–they were already near the global summit of income and have remained there–but the poorer citizens who have become substantially worse off in relative terms. Germany went from having a national income “spread” between the 83rd and 99th percentiles in 1993 to one running from the 75th to the 100th percentile in 2018. Despite being the world’s fourth largest economy and the export powerhouse of Europe, Germany’s weakest inhabitants nonetheless fell nearly a decile down the global income ladder.

Sliding into separate societies

Why should such statistical findings matter? Milanovic postulates an implicit premise: democratic systems cannot survive being stretched across larger swathes of the global income distribution without experiencing severe political stress. He argues that this is mainly because in a globalized world dominated by advertisement driven social media, certain standards for what constitutes the good life for a worldly consumer take hold. Richer Asians and lower- and middle-class Europeans are increasingly competing for status-signifying positional goods such as holidays in Thailand, tickets to the World Cup, and the latest smartphone model.

I am not entirely sure that this shift in relative self-evaluation explains the revolt of the Western lower classes. A more straightforward and simple explanation is that the Western losers of globalization correctly perceive that they are living in a material band of well-being that is further and further removed from that in which the richest citizens of their own countries–compatriots with whom they supposedly share equal rights and democratic institutions but whose lifestyle and affluence puts them on what might as well be another planet.

In sum, Western societies are under serious stress because their richest and poorest members are no longer living in the same “country,” in the sense of a coherent, discrete section of the global income ladder. They live in separate global classes and societies. And they are angry at those who have improved their own elite bubble while their own environment has become visibly worse off.

Whatever one thinks of Milanovic’s preferred causal mechanism between shifts in the income distribution and political upheaval, his findings are incredibly striking and powerful. To my mind the facts he marshals must now stand as the basic parameters of any political and historical attempt to explain the “backlash” against neoliberalism and the global economic system that defined the period between 1979 and 2016.

The income divergence that Milanovic observes in Western societies is not as marked in the fastest-growing major economy at the heart of global convergence: China. Since the end of the Cold War the bandwidth of urban Chinese incomes moved substantially up the global distribution. whereas it ran from the 18th to the 66th percentile in 1988, some thirty years later it had ratcheted up the ladder from the 39th to the 93rd percentile. Rich Chinese citizens improved their lot more than poor ones, which is consistent with the widening of intra-national income inequality in China since the Reform and Opening Up period began. But despite China spanning a very large section of global outcomes, even the poorest Chinese have undeniably become substantially better off.

Openness without laissez-faire

Was this coincidence of Western immiseration and Asian growth inevitable? Milanovic claims they were not. A better-managed system of globalization should have included Western policies that explicitly sought to compensate the working- and middle-class losers generated by offshoring. This would have involved steeper progressive taxation of the Western rich to funnel income from the growing top to the left-behind middle, as well as retraining programs, and expanded healthcare, educational and social policies to sustain social cohesion and preserve broad-based income and human development gains. (I have previously made this argument with regard to the distributional consequences of U.S. trade policy at greater length in the pages of the Yale Review.)

But despite the technical possibility of such a policy, strong political and ideological forces were pushing in the opposite direction: towards lower taxes, less government, and a general validation of market-produced outcomes. Unfair globalization was not inevitable, but due to the influence of neoliberal ideology it became politically all but inevitable. Since dominant Western governments, institutions, politicians and thinkers equated laissez-faire with global economic openness, a more measured approach that would have separated the two was inconceivable for many in the West.

It is worth pointing out that one hundred years ago, Western liberal leaders had less difficulty seeing laissez-faire and free trade as distinct policies that could be moderated and modulated independently of one another. Lloyd George’s New Liberalism, for example, was a powerful populist liberal agenda that delivered a landslide election for the British Liberal Party in 1906 after more than a decade of Conservative rule. It was a vision in which rich and civilized states should reap the benefits of free trade and openness, but guard against social unrest by enabling the state to be more, not less, interventionist in matters of taxation, regulation, and social provision. But there is no policy platform akin to it in the recent European and American past. Late twentieth-century neoliberalism as it developed in the wake of Thatcher and Reagan equated all efforts to foster greater domestic equality with protectionist heresies against openness.

This impulse to lump together (protectionism and interventionism has set us up for a worse outcome in the age of backlash against the liberal free-trade order. Openness has everywhere been assaulted and weakened, while laissez-faire survives unscathed. In many cases Western citizens now face the worst of both worlds: no more economic, cultural and political benefits of exchange from abroad, and a viciously Darwinian capitalism with minimal social protection at home. This is what Milanovic describes as the bad world of “national market liberalism” that we are entering.

National Market Liberalism and Relative Autonomy

Asian states have not escaped the backlash, Milanovic notes. In both China and Russia, new authoritarian currents have surfaced that react against the inequality-accelerating forces of openness and rapid growth. Putin’s regime consolidated power thanks to popular resentment towards oligarchs and anger about Western-backed shock therapy in the 1990s, even if its subsequent policy up until 2022 has been, I would argue, very much in line with an austerity-focused orthodox neoliberal doctrine (on this I would recommend Tony Wood’s Russia Without Putin, a slim 2018 volume that remains the sharpest analysis of the socio-economic foundations of Putinist Russia that I know of).

In China, Xi Jinping has governed a society in which inequality is at much greater levels than ever before in the history of a self-described communist state. He has cut tech entrepreneurs down to size, emphasized “common prosperity,” and launched large-scale anti-corruption purges. Ostensibly this places Trump, Putin, and Xi in the same camp as exponents of a new post-global national market liberalism.

Yet there is an important catch in the Chinese story, one that connects it to Chen and Westad’s study of Chinese reform. For despite its great inequality, Xi’s China is one of the only states that does seem to have made some effort to curb elite incomes and rein in its domestic winners of globalization. To show this, Milanovic marshals his research into Xi’s anti-corruption purges together with Li Yang and Yaoqi Lin.

By studying the biographies of 828 senior officials purged between 2012 and 2021, Milanovic, Yang and Lin find that some 82 percent of those convicted in the anti-corruption purges are in the richest 1 percent of urban Chinese households, and every single one is in the top 5 percent. The campaign to curb abuse has thus overwhelmingly targeted the Chinese red bourgeoisie.

One should be wary of jumping to big conclusions about Xi’s socioeconomic goals: many extremely wealthy private individuals exist in China, there are confounding political motives, and no concerted agenda for class equalization or sustained income compression has arisen. But the elite focus of the purges nonetheless suggests that the People’s Republic of China may be alone among the new trio of Great Powers in possessing a degree of genuine state autonomy that can discipline capital and keep powerful elites in check.

The Long NEP hypothesis

The question is how to interpret this relative autonomy of the state vis-à-vis the elite. There are deep roots for this in Marxist thinking and in the highly organized practice of Communist party organizations, of course. Milanovic does not ignore these. Indeed, one of The Great Global Transformation’s virtues is that it spends a lot of time on ideology. Milanovic himself has previously suggested that we might see the entire Reform and Opening Up period since 1978 as a very long Chinese version of the Soviet New Economic Policy of the 1920s: a capitulation to market forces that is meant to be temporary and instrumental, intended to strengthen and enrich China so that it can fulfill its ideological mission with greater power in the future.

On this line of argument, China did not abandon any of its old Maoist goals in the 1970s, but simply picked different means by which to pursue them. Those in the West who lauded Deng Xiaoping for steering China away from state socialism and towards free markets did not appreciate that the CCP did not inherently care about capitalism: it was undertaking a tactical shift to continue to move towards the same long-term objective of enhancing Chinese power. Viewed in the fullness of twentieth-century history, Chinese reform was about a change in tactics, not a shift in strategy.

This hypothesis imputes a great deal of intention and consistency to the Chinese Communist Party: to wit, that the greatest socioeconomic takeoff in modern history was just an improved gear shift in an ulterior project to pursue Chinese-style socialism by other means. As Deng Xiaoping put it on his famous Southern Tour in 1992:

Feudal society replaced slave society, capitalism supplanted feudalism, and, after a long time, socialism will necessarily supersede capitalism. This is an irreversible general trend of historical development, but the road has many twists and turns. Over the several centuries that it took for capitalism to replace feudalism, how many times were monarchies restored! So, in a sense, temporary restorations are usual and can hardly be avoided.

Some countries have suffered major setbacks, and socialism appears to have been weakened. But the people have been tempered by the setbacks and have drawn lessons from them, and that will make socialism develop in a healthier direction. So don’t panic, don’t think that Marxism has disappeared, that it’s not useful any more and that it has been defeated. Nothing of the sort!

We shall push ahead along the road to Chinese-style socialism. Capitalism has been developing for several hundred years. How long have we been building socialism? Besides, we wasted twenty years. If we can make China a moderately developed country within a hundred years from the founding of the People’s Republic, that will be an extraordinary achievement. The period from now to the middle of the next century will be crucial.

There is in Deng’s words a powerful and explicit appeal to the long-run sweep of history–an arc only visible across decades and centuries.

One might object that history is far too contingent to make such a long-run strategy plausible. But there may well be good reasons to take ideology quite seriously in the Chinese case. For one thing, as Milanovic points out, Xi has targeted as his opponents those who he accuses of being “ideological nihilists”. By this he means party officials who have no overarching values other than their own personal power and self-enrichment. Allowing such nihilists near the levers of power was, in Xi’s view, the fatal mistake made by the Soviet Communist Party, which disintegrated into an orgy of kleptocracy and infighting in the late 1980s and brought down the Soviet Union along with it.

Another reason for considering the long NEP hypothesis is the fact that Chinese economic policy was, even in the socialist heyday under Mao from 1949 to 1976, more pragmatic and flexible than is often assumed. Indeed, Xi’s favorite slogan “common prosperity” was used by Mao in 1953 and also featured in Deng’s thinking as “the highest stage in the long-run economic development of China” (p. 239n29). While these three leaders are often portrayed as highly distinct from each other, they had much in common in their basic assumptions, style of rule, and political commitments. Both Milanovic and Chen and Westad’s books show that these continuities run much deeper than is acknowledged in most Western commentary on China.

The pitfall of economic reductionism

It is worth asking why these commonalities were not more obvious to foreigners. Neoliberal ideology in the West is certainly part of the answer. After the 1970s, economics came to pervade most Western thinking about politics. In Europe and the United States there was little debate about political ends: what else was politics about but finding the best ways to deregulate, let the market rip, and chase GDP growth for its own sake, distribution be damned?

Ironically, many left-wing critics of China abroad shared with the neoliberals this focus on economic outcomes. For them the problem was the opposite: China had betrayed the cause of real socialism and was practicing brutal capitalism while still professing to pursue the revolution. This view is similar to Trotsky’s leftist criticisms of the New Economic Policy in the 1920s Soviet leadership: it was treason against philosophical principles that could only be implemented wholesale.

Thus the entire Reform and Opening Up period is portrayed by some analysts as one long counter-revolution against Maoism. But as Milanovic suggests, the material results make it hard to deny that some good came out of the whole reform era, not least in the remarkable growth in wellbeing and human development that it has unleashed.

Both neoliberal and leftist perspectives on China thus missed something important because they had the wrong presupposition about the relationship between politics and economics. The former could not be reduced to the latter. For Chinese communist leaders, however, economics was always a more instrumental realm than a domain of ends in themselves. There is plenty of evidence for this in the period that Westad and Chen examine–the 1960s to the 1980s-and to which we will turn next week, in the second part of this review.

But what if the original low spread in Italy's (and West's in general) income distribution vs world's income distribution was just a by-product of the exploitation of the rest of the world? The dominance on the global stage could allow the redistribution to consolidate power from an internal politics POV. We observe China catching up since it started vey far, that their recipe would be successful in the future is another matter. Maybe a high-redistribution approach is not competitve on the global stage, at least the relative decline of the influence of european nations with respect to the US seems a hint in that direction

How anyone can believe that the solution to inequality could have been "more transfers", given the scale of our current transfers, is beyond me. I do not refute the main thesis, status signals are powerful, but the counterfactual Is weak